Verse 9: He who is not free from taints of moral defilements (kilesas) and yet dons the yellow robe, who lacks restraint in his senses and (speaks not the) truth is unworthy of the yellow robe.

Verse 10: He who has discarded all moral defilements (kilesas), who is established in moral precepts, is endowed with restraint and (speaks the) truth is, indeed, worthy of the yellow robe.

1. kasavam or kasavam vattham: the yellow or reddish yellow robe donned by members of the Buddhist Religious Order. There is a play on words in the above stanzas; ‘anikkasavo’, meaning, not free from faults of moral defilements and therefore, stained; and kasavam, the yellow robe, dyed sombre in some astringent juice and is therefore stained.

2. vantakasav’assa: lit., has vomited all moral defilements; it means, has discarded all moral defilements through the four Path Knowledge (Magga nana).

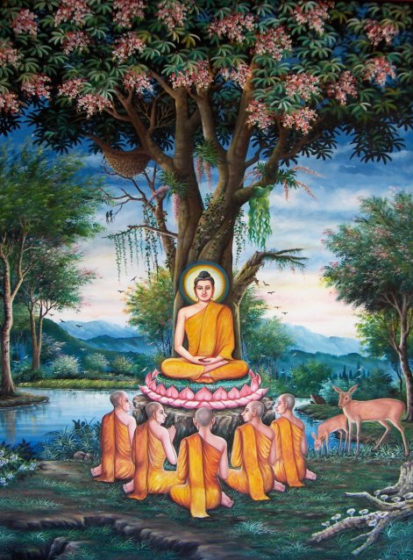

While residing at the Jetavana monastery in Savatthi, the Buddha uttered Verses (9) and (10) of this book, with reference to Devadatta.

Once the two Chief Disciples, the Venerable Sariputta and the Venerable Maha Moggallana, went from Savatthi to Rajagaha. There, the people of Rajagaha invited them, with their one thousand followers, to a morning meal. On that occasion someone handed over a piece of cloth, worth one hundred thousand, to the organizers of the alms-giving ceremony. He instructed them to dispose of it and use the proceeds for the ceremony should there be any shortage of funds, or if there were no such shortage, to offer it to anyone of the bhikkhus they thought fit. It so happened that there was no shortage of anything and the cloth was to be offered to one of the theras. Since the two Chief Disciples visited Rajagaha only occasionally, the cloth was offered to Devadatta, who was a permanent resident of Rajagaha.

Devadatta promptly made the cloth into robes and moved about pompously, wearing them. Then, a certain bhikkhu from Rajagaha came to Savatthi to pay homage to the Buddha, and told him about Devadatta and the robe, made out of cloth worth one hundred thousand. The Buddha then said that it was not the first time that Devadatta was wearing robes that he did not deserve. The Buddha then related the following story.

Devadatta was an elephant hunter in one of his previous existences. At that time, in a certain forest, there lived a large number of elephants. One day, the hunter noticed that these elephants knelt down to the paccekabuddhas* on seeing them. Having observed that, the hunter stole an upper part of a yellow robe and covered his body and hand with it. Then, holding a spear in his hand, he waited for the elephants on their usual route. The elephants came, and taking him for a paccekabuddha fell down on their knees to pay obeisance. They easily fell prey to the hunter. Thus, one by one, he killed the last elephant in the row each day for many days.

The Bodhisatta (the Buddha-to-be) was then the leader of the herd. Noticing the dwindling number of his followers he decided to investigate and followed his herd at the end of the line. He was alert, and was therefore able to evade the spear. He caught hold of the hunter in his trunk and was about to dash him against the ground, when he saw the yellow robe. Seeing the yellow robe, he desisted and spared the life of the hunter.

The hunter was rebuked for trying to kill under cover of the yellow robe and for commuting such an act of depravity. The hunter clearly did not deserve to put on the yellow robe.

Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 9: He who is not free from taints of moral defilements (kilesas) and yet dons the yellow robe, who lacks restraint in his senses and (speaks not the) truth is unworthy of the yellow robe.

Verse 10: He who has discarded all moral defilements (kilesas), who is established in moral precepts, is endowed with restraint and (speaks the) truth is, indeed, worthy of the yellow robe.

At the end of the discourse, many bhikkhus were established in Sotapatti Fruition.

* Paccekabuddha: One who, like the Buddha, is Self-Enlightened in the Four Noble Truths and has uprooted all the moral defilements (kilesas). However, he cannot teach others. Paccekabuddhas appear during the absence of the Buddha Sasana (Teaching).

Dhammapada Verses 9 and 10

Devadatta Vatthu

Anikkasavo kasavam1

yo vattham paridahissati

apeto damasaccena

na so kasavamarahati.

Yo ca vantakasav’assa2

silesu susamahito

upeto damasaccena

sa ve kasavamarahati.

Source: Tipitaka