The Story of Five Hundred Bhikkhus

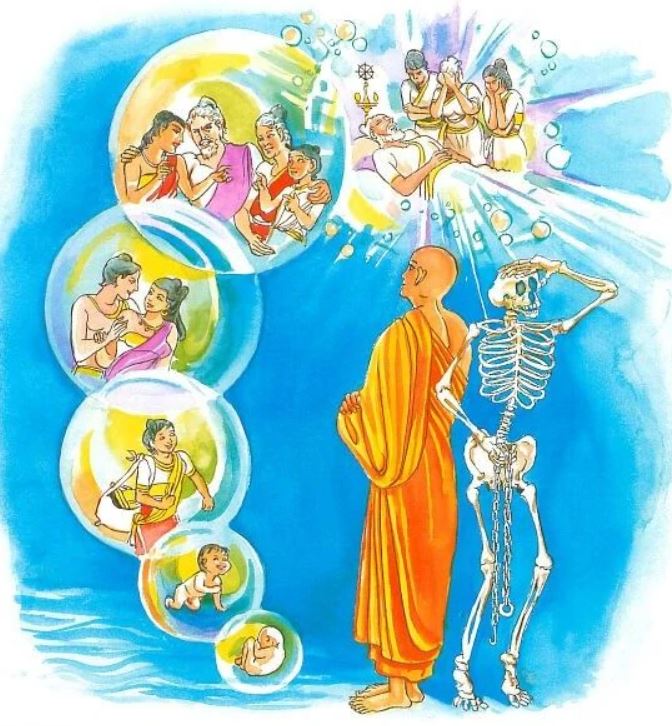

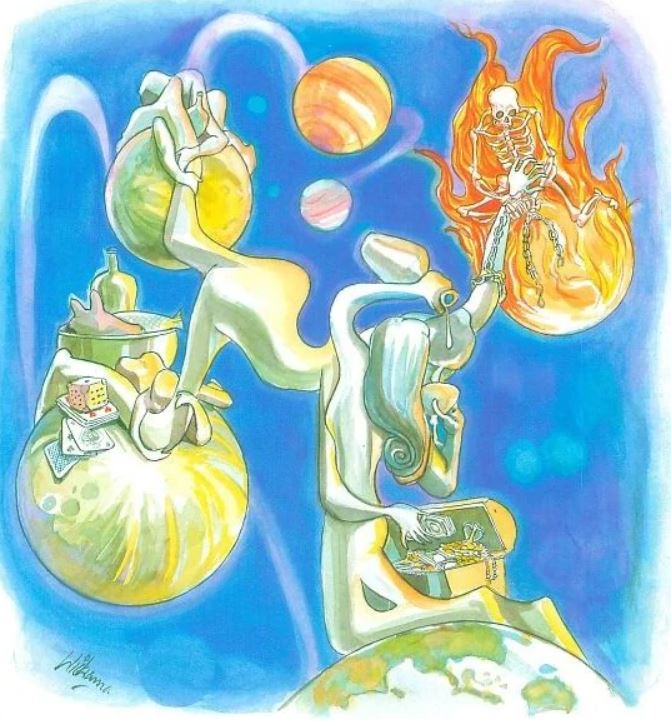

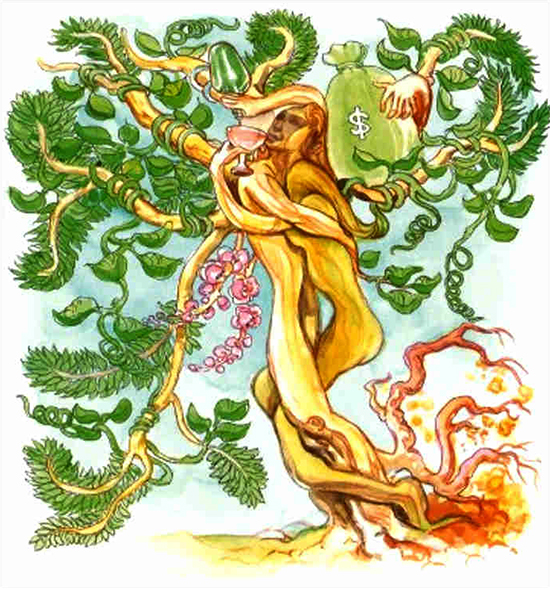

Verse 170: If a man looks at the world (i.e., the five khandhas) in the same way as one looks at a bubble or a mirage, the King of Death will not find him.

- evam jokam avekkhantam: one who looks at the world in the same way, i.e., looks at the world as being impermanent as a bubble and as non-material as a mirage.

The Story of Five Hundred Bhikkhus

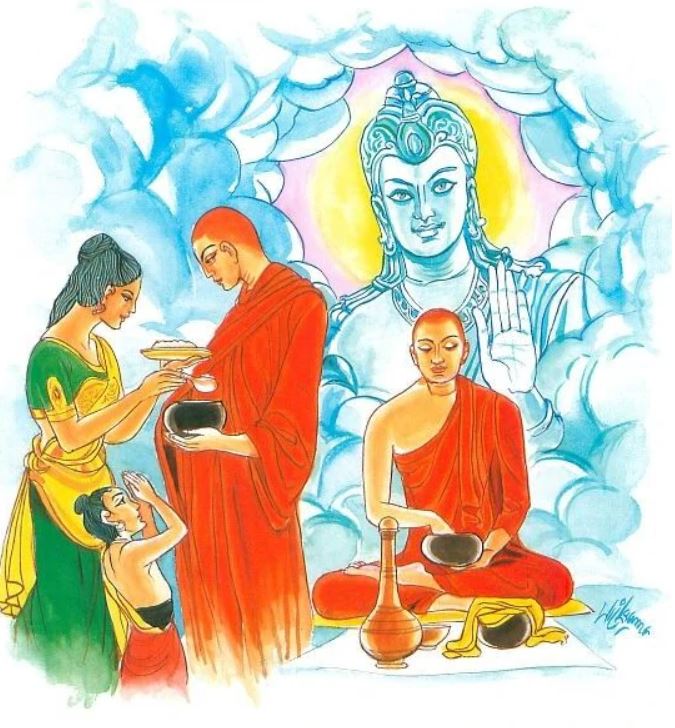

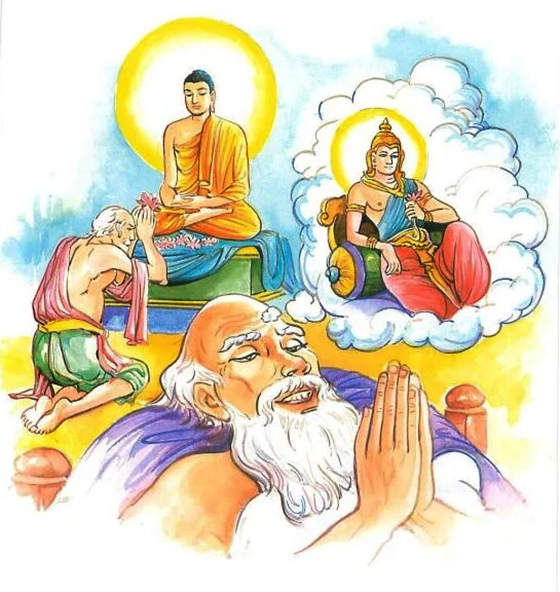

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (170) of this book, with reference to five hundred bhikkhus.

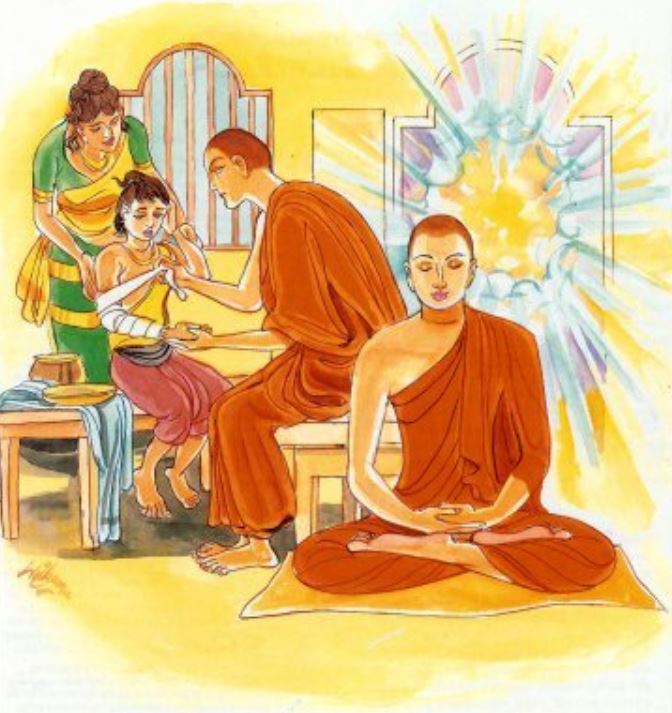

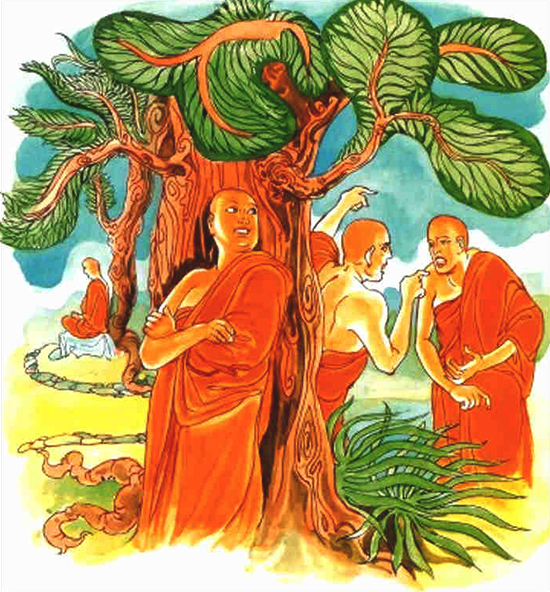

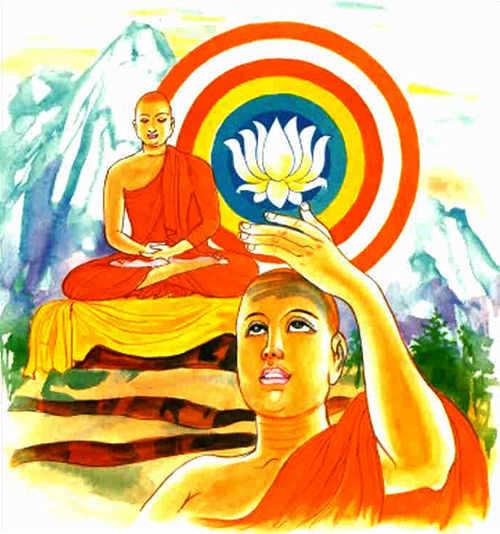

On one occasion, five hundred bhikkhus, after taking a subject of meditation from the Buddha, went into the forest to practise meditation. But they made very little progress; so they returned to the Buddha to ask for a more suitable subject of meditation. On their way to the Buddha, seeing a mirage they meditated on it. As soon as they entered the compound of the monastery, a storm broke out; as big drops of rain fell, bubbles were formed on the ground and soon disappeared. Seeing those bubbles, the bhikkhus reflected “This body of ours is perishable like the bubbles”, and perceived the impermanent nature of the aggregates (khandhas).

The Buddha saw them from his perfumed chamber and sent forth the radiance and appeared in their vision. Continue reading