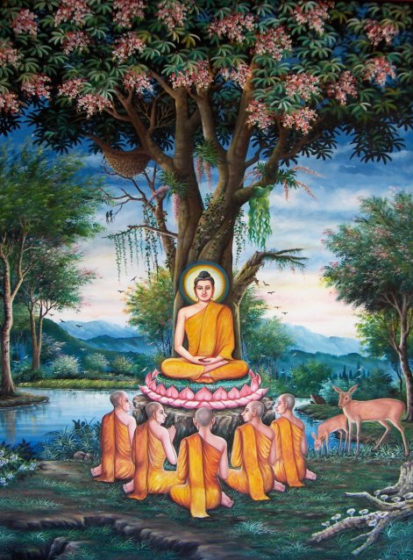

Verse 21: Mindfulness is the way to the Deathless (Nibbana); unmindfulness is the way to Death. Those who are mindful do not die; those who are not mindful are as if already dead.

Verse 22: Fully comprehending this, the wise, who are mindful, rejoice in being mindful and find delight in the domain of the Noble Ones (Ariyas).

Verse 23: The wise, constantly cultivating Tranquillity and Insight Development Practice, being ever mindful and steadfastly striving, realize Nibbana: Nibbana, which is free from the bonds of yoga; Nibbana, the Incomparable!

1. appamada: According to the Commentary, it embraces all the meanings of the words of the Buddha in the Tipitaka, and therefore appamada is to be interpreted as being ever mindful in doing meritorious deeds; to be in line with the Buddha’s Teaching in Mahasatipatthana Sutta, “appamado amatapadam”, in particular, is to be interpreted as “Cultivation of Insight Development Practice is the way to Nibbana.”

2. amata: lit., no death, deathless; it does not mean eternal life or immortality. The Commentary says: “Amata means Nibbana. It is true that Nibbana is called “Amata” as there is no ageing (old age) and death because there is no birth.”

3. pamado maccuno padam: lit., unmindfulness is the way to Death. According to the Commentary, one who is unmindful cannot be liberated from rebirth; when reborn, one must grow old and die; so unmindfulness is the cause of Death.

4. appamatta na miyanti: Those who are mindful do not die. It does not mean that they do not grow old or die. According to the Commentary, the mindful develop mindful signs (i.e., cultivate Insight Development Practice); they soon realize Magga-Phala (i.e., Nibbana) and are no longer subject to rebirths. Therefore, whether they are, in fact, alive or dead, they are considered not to die.

5. ye pamatta yatha mata: as if dead. According to the Commentary, those who are not mindful are like the dead; because they never think of giving in charity, or keeping the moral precepts, etc., and in the case of bhikkhus, because they do not fulfil their duties to their teachers and preceptors, nor do they cultivate Tranquillity and Insight Development Practice.

6. ariyanam gocare rata: lit., “finds delight in the domain of the ariyas.” According to the Commentary the domain of the ariyas consists of the Thirty-seven Factors of Enlightenment (Bodhipakkhiya) and the nine Transcendentals, viz., the four Maggas, the four Phalas, and Nibbana.

7. jhiyino: those cultivating Tranquillity and Insight Development Practice.

8. phusanti dhira nibbanam: the wise realize Nibbana. Lit., phusati means, to touch, to reach. According to the Commentary, the realization takes place, through contact or experience, which may be either through Insight (Magga-Nana) or through Fruition (Phala). In this context, contact by way of Fruition is meant.

9. yogakkhemam: an attribute of Nibbana. Lit., it means free or secure from the four bonds which bind people to the round of rebirths. The four bonds or yoga are: sense pleasures (kama), existence (bhava), wrong belief (ditthi), and ignorance of the Four Noble Truths (avijja).

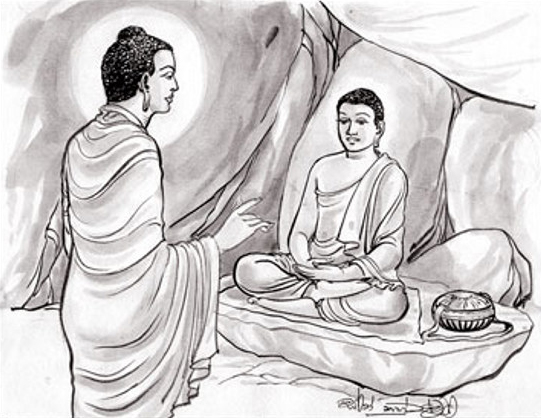

While residing at the Ghosita monastery near Kosambi, the Buddha uttered Verses (21), (22) and (23) of this book, with reference to Samavati, one of the chief queens of Udena, King of Kosambi.

Samavati had five hundred maids-of-honour staying with her at the palace; she also had a maid servant called Khujjuttara. The maid had to buy flowers for Samavati from the florist Sumana everyday. On one occasion, Khujjuttara had the opportunity to listen to a religious discourse delivered by the Buddha at the home of Sumana and she attained Sotapatti Fruition. She repeated the discourse of the Buddha to Samavati and the five hundred maids-of-honour, and they also attained Sotapatti Fruition. From that day, Khujjuttara did not have to do any menial work, but took the place of mother and teacher to Samavati. She listened to the discourses of the Buddha and repeated them to Samavati and her maids. In course of time, Khujjuttara mastered the Tipitaka. Continue reading →