Verse 35: The mind is difficult to control; swiftly and lightly, it moves and lands wherever it pleases. It is good to tame the mind, for a well-tamed mind brings happiness.

1. yatthakamanipatino: moving about wherever it pleases, landing on any sense object without any control.

2. sukhavaham: brings happiness, fortune, satisfaction, etc., and also, Maggas, Phalas and Nibbana. (The Commentary)

The Story of A Certain Bhikkhu

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (35) of this book, with reference to a certain bhikkhu.

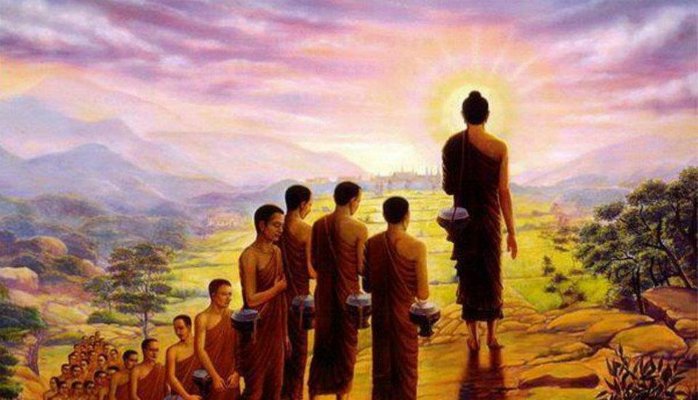

On one occasion, sixty bhikkhus, after obtaining a subject of meditation from the Buddha, went to Matika village, at the foot of a mountain. There, Matikamata, mother of the village headman, offered them alms-food; she also built a monastery for them, so that they could stay in the village during the rainy season. One day she asked the group of bhikkhus to teach her the practice of meditation. They taught her how to meditate on the thirty-two constituents of the body leading to the awareness of the decay and dissolution of the body. Matikamata practised with diligence and attained the three Maggas and Phalas together with Analytical Insight and mundane supernormal powers, even before the bhikkhus did.

Rising from the bliss of the Magga and Phala she looked with the Divine Power of Sight (Dibbacakkhu) and saw that the bhikkhus had not attained any of the Maggas yet. She also learnt that those bhikkhus had enough potentiality for the attainment of arahatship, but that they needed proper food. So, she prepared good, choice food for them. With proper food and right effort, the bhikkhus developed right concentration and eventually attained arahatship.

At the end of the rainy season, the bhikkhus returned to the Jetavana monastery, where the Buddha was in residence. They reported to the Buddha that all of them were in good health and in comfortable circumstances and that they did not have to worry about food. They also mentioned about Matikamata who was aware of their thoughts and prepared and offered them the very food they wished for.

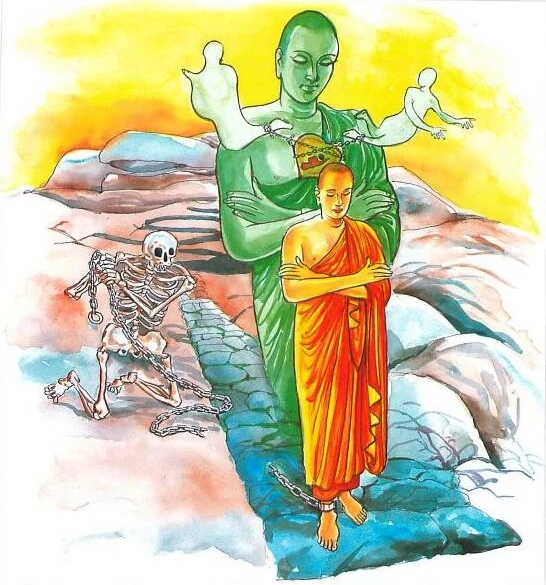

A certain bhikkhu, hearing them talking about Matikamata, decided that he, too, would go to that village. So, taking a subject of meditation from the Buddha he arrived at the village monastery. There, he found that everything he wished for was sent to him by Matikamata, the lay-devotee. When he wished her to come she personally came to the monastery, bringing along choice food with her. After taking the food, he asked her if she knew the thoughts of others, but she evaded his question and replied, “People who can read the thoughts of others behave in such and such a way.” Then, the bhikkhu thought, “Should I, like an ordinary worldling, entertain any impure thought, she is sure to find out.” He therefore got scared of the lay-devotee and decided to return to the Jetavana monastery. He told the Buddha that he could not stay in Matika village because he was afraid that the lay-devotee might detect impure thoughts in him. The Buddha then asked him to observe just one thing; that is, to control his mind. The Buddha also told the bhikkhu to return to Matika village monastery, and not to think of anything else, but the object of his meditation only. The bhikkhu went back. The lay-devotee offered him good food as she had done to others before, so that he might able to practise meditation without worry. Within a short time, he, too, attained arahatship.

With reference to this bhikkhu, the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 35: The mind is difficult to control; swiftly and lightly, it moves and lands wherever it pleases. It is good to tame the mind, for a well-tamed mind brings happiness.

At the end of the discourse, many of those assembled attained Sotapatti Fruition.

Dhammapada Verse 35

Annatarabhikkhu Vatthu

Dunniggahassa lahuno

yatthakamanipatino1

cittassa damatho sadhu

cittam dantam sukhavaham2.

Source: Tipitaka