The first question, on entering the completed interior of the church of Sagrada Família, is: “Is it really there?” We have been so long accustomed to the idea that Barcelona’s most famous landmark is a permanent ruin, unfinished and unfinishable, that it comes as a shock to find it is now keeping out the weather. Source: Rowan Moore, The Guardian

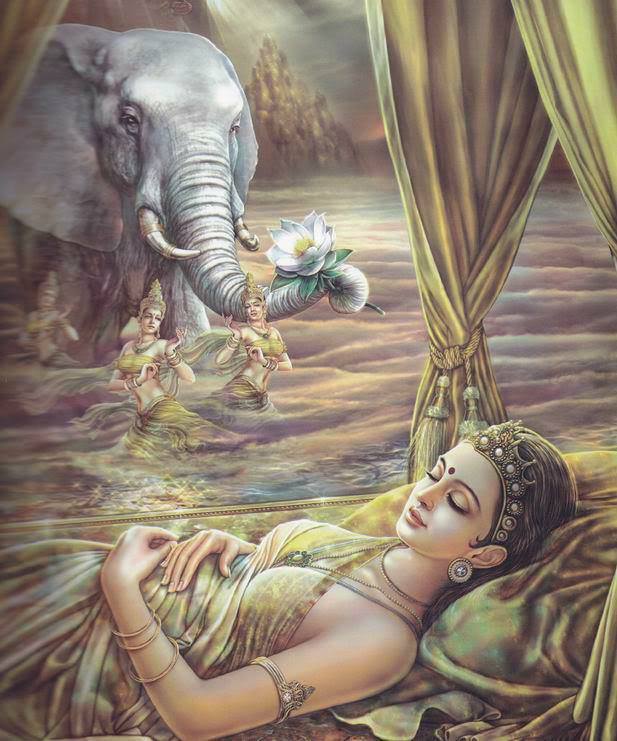

La Sagrada Familia. Photo credit: School of Vice/KI Media

The expiatory church of La Sagrada Família is a work on a grand scale which was begun on 19 March 1882 from a project by the diocesan architect Francisco de Paula del Villar (1828-1901). At the end of 1883 Gaudí was commissioned to carry on the works, a task which he did not abandon until his death in 1926. Since then different architects have continued the work after his original idea.

The building is in the centre of Barcelona, and over the years it has become one of the most universal signs of identity of the city and the country. It is visited by millions of people every year and many more study its architectural and religious content.

It has always been an expiatory church, which means that since the outset, 133 years ago now, it has been built from donations. Gaudí himself said: “The expiatory church of La Sagrada Família is made by the people and is mirrored in them. It is a work that is in the hands of God and the will of the people.” The building is still going on and could be finished some time in the first third of the 21st century. Source: Sagrada Familia.cat

Photo credit: School of Vice/KI Media

When the final stone is set in place, the Sagrada Família will be the world’s tallest church, soaring 560-ft (170-m) above the Catalan capital. It will also be the strangest looking and possibly the most controversial place of worship ever built on such an epic scale. Looking for all the world like a cluster of gigantic stone termites’ nest, a colossal vegetable patch, a gingerbread house baked by the wickedest witch of all or perhaps a petrified forest, this hugely ambitious church has confounded architects, critics and historians ever since its unprecedented shape became apparent soon after World War I. Continue reading →