-

Nature unfolds her treasure Comment October 15, 2022 -

The Bhikkhus’ Rules 2 October 14, 2022

Bhikkhu Buddha Saddha Vey Ve, Bhikkhu Indajoto and Samanera Ananda at the Kiryvongsa Bopharam Buddhist Temple, the Peace Meditation Center.

The Teaching of the Buddha is concerned with more than intellectual knowledge for it needs to be experienced as truth in one’s own life. The Buddha often called his Teaching the Dhamma-Vinaya and when he passed away he left these as the guide for all of us who followed. As Venerable Thiradhammo writes:

In simple terms we could say that while Dhamma represented the principles of Truth, the Vinaya represented the most efficacious lifestyle for the realization of that Truth. Or, the Vinaya was that way of life which enshrined the principles of Truth in the practicalities of living within the world.” (HS Part 2)

For the bhikkhu, the Vinaya helps to highlight actions and speech, and show up their significance. It brings an awareness of how he is intervening in the world, how he is affecting other people. For better? For worse? With what intention?Of course, such an awareness is necessary for every human being, not just Buddhist monks. This is why the Buddha bequeathed to us the Five, the Eight and the Ten Precepts — as well as the bhikkhu’s 227 rules of the Paatimokkha. These precepts and rules remain as pertinent today as they were 2,500 years ago for they restore the focus back to the human being, to how actions and words affect individuals and the world. While the particulars may have changed, the fundamentals remain the same. Continue reading

-

Stressing and complaining will change nothing Comment October 14, 2022“Happiness comes a lot easier when you stop complaining about your problems and you start being grateful for all the problems you don’t have.”

“Happy are they who take life day by day, complain very little and are thankful for the little things in life.”

“Complaining is a complete waste of one’s energy. Those who complain the most accomplish the least.”

“As you breathe right now, another takes his last. So stop complaining and learn to live with what you have.”~ Anonymous Continue reading

-

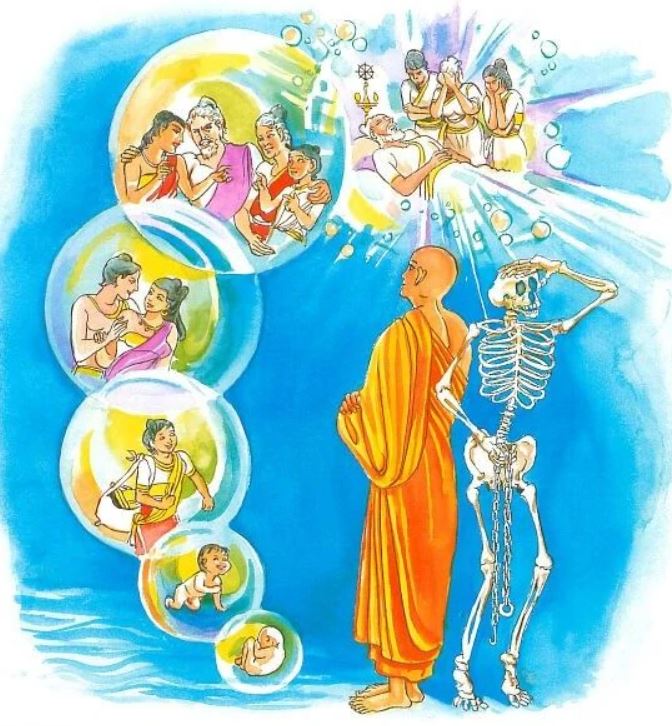

The Story of Five Hundred Bhikkhus 6 March 22, 2022Verse 170: If a man looks at the world (i.e., the five khandhas) in the same way as one looks at a bubble or a mirage, the King of Death will not find him.

- evam jokam avekkhantam: one who looks at the world in the same way, i.e., looks at the world as being impermanent as a bubble and as non-material as a mirage.

The Story of Five Hundred Bhikkhus

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (170) of this book, with reference to five hundred bhikkhus.

On one occasion, five hundred bhikkhus, after taking a subject of meditation from the Buddha, went into the forest to practise meditation. But they made very little progress; so they returned to the Buddha to ask for a more suitable subject of meditation. On their way to the Buddha, seeing a mirage they meditated on it. As soon as they entered the compound of the monastery, a storm broke out; as big drops of rain fell, bubbles were formed on the ground and soon disappeared. Seeing those bubbles, the bhikkhus reflected “This body of ours is perishable like the bubbles”, and perceived the impermanent nature of the aggregates (khandhas).

The Buddha saw them from his perfumed chamber and sent forth the radiance and appeared in their vision. Continue reading

-

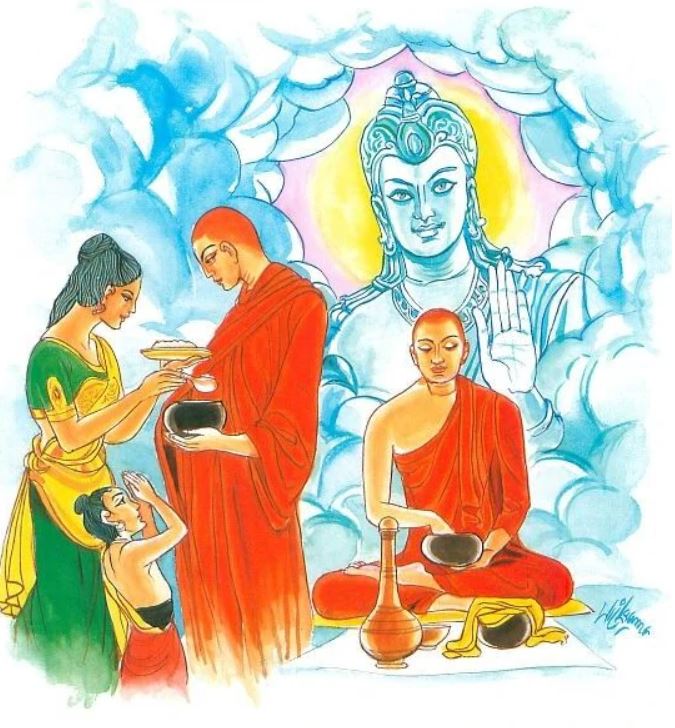

The Story of King Suddhodana 1 January 25, 2022Verse 168: Do not neglect the duty of going on alms-round; observe proper practice (in going on alms-round). One who observes proper practice lives happily both in this world and in the next.

Verse 169: Observe proper practice (in going on alms-round); do not observe improper practice. One who observes proper practice lives happily both in this world and in the next.

- dhammam sucaritam: proper practice. The Commentary says that here proper practice means stopping for alms-food at one house after another in the course of the alms-round except where it is not proper to go (such as a courtesan’s house).

-

na nam duccaritam: improper practice. Here it means not observing the above rules.

The Story of King Suddhodana

While residing at the Nigrodharama monastery, the Buddha uttered Verses (168) and (169) of this book, with reference to King Suddhodana, father of Gotama Buddha. Continue reading

-

Anxiety, heartbreak, and tenderness 5 January 20, 2022Anxiety, heartbreak, and tenderness mark the in-between state. It’s the kind of place we usually want to avoid. The challenge is to stay in the middle rather than buy into struggle and complaint. The challenge is to let it soften us rather than make us more rigid and afraid. Becoming intimate with the queasy feeling of being in the middle of nowhere only makes our hearts more tender. When we are brave enough to stay in the middle, compassion arises spontaneously. By not knowing, not hoping to know, and not acting like we know what’s happening, we begin to access our inner strength. ~ Pema Chödron

-

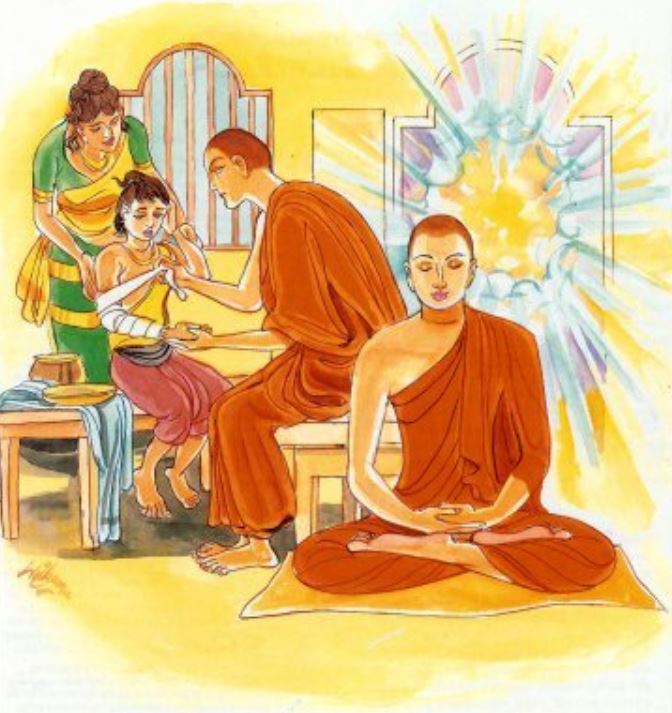

The Story of a Young Bhikkhu Comment January 19, 2022Verse 167: Do not follow ignoble ways, do not live in negligence, do not embrace wrong views, do not be the one to prolong samsara (lit., the world).

The Story of a Young Bhikkhu

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (167) of this book, with reference to a young bhikkhu.

Once, a young bhikkhu accompanied an older bhikkhu to the house of Visakha. After taking rice gruel, the elder bhikkhu left for another place, leaving the young bhikkhu behind at the house of Visakha. The granddaughter of Visakha was filtering some water for the young bhikkhu, and when she saw her own reflection in the big water pot she smiled. Seeing her thus smiling, the young bhikkhu looked at her and he also smiled. When she saw the young bhikkhu looking at her and smiling at her, she lost her temper, and cried out angrily, “You, a shaven head! Why are you smiling at me ?” The young bhikkhu reported, “You are a shaven head yourself; your mother and your father are also shaven heads!” Thus, they quarrelled, and the young girl went weeping to her grandmother. Visakha came and said to the young bhikkhu, “Please do not get angry with my grand daughter. But, a bhikkhu does have his hair shaved, his finger nails and toe nails cut, and putting on a robe which is made up of cut pieces, he goes on alms-round with a bowl which is rimless. What this young girl said was, in a way, quite right, is it not?” The young bhikkhu replied. “It is true but why should she abuse me on that account ?” At this point, the elder bhikkhu returned; but both Visakha and the old bhikkhu failed to appease the young bhikkhu and the young girl.

Soon after this, the Buddha arrived and learned about the quarrel. The Buddha knew that time was ripe for the young bhikkhu to attain Sotapatti Fruition. Then, in order to make the young bhikkhu more responsive to his words, he seemingly sided with him and said to Visakha, “Visakha, what reason is there for your grand daughter to address my son as a shaven head just because he has his head shaven? After all, he had his head shaven to enter my Order, didn’t he?” Continue reading

-

How you perceive the situation 1 January 19, 2022 -

The Story of Thera Attadattha 3 January 5, 2022Verse 166: For the sake of another’s benefit, however great it may be, do not neglect one’s own (moral) benefit. Clearly perceiving one’s own benefit one should make every effort to attain it.

- Attadattham: one’s own benefit. According to the Commentary, in this context, one’s own benefit means Magga, Phala and Nibbana. (N.B. The above was uttered by the Buddha in connection with Insight Meditation.)

The Story of Thera Attadattha

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (166) of this book, with reference to Thera Attadattha.

When the Buddha declared that he would realize parinibbana in four months’ time, many puthujjana bhikkhus* were apprehensive and did not know what to do; so they kept close to the Buddha. Attadattha, however, did not go to the Buddha and, having resolved to attain arahatship during the lifetime of the Buddha, was striving hard in the meditation practice. Other bhikkhus, not understanding him, took him to the Buddha and said, “Venerable Sir, this bhikkhu does not seem to love and revere you as we do; he only keeps to himself.” The thera then explained to them that he was striving hard to attain arahatship before the Buddha realized parinibbana and that was the only reason why he had not come to the Buddha. Continue reading

-

We should not say bad things about anyone 5 November 17, 2021We should not say bad things about anyone, whether or not they are bodhisattvas. It is not the same thing, however, if we know that pointing out someone’s mistakes will help them to change. Generally speaking, since it is not easy to change another person, we should avoid criticism. Other people do not like to hear it and, further, laying out their faults will create problems and troubles for us. We who are supposed to be practicing the dharma should be trying to do whatever brings happiness to ourselves and others. Since faultfinding does not bring any benefit, we should carefully avoid it.

If we really want to help someone, perhaps we can say something once in a pleasant way so that the person can readily understand, “Oh yes, this is something I need to change.” However, it is better not to repeat our comments, because if we keep mentioning faults, not only will it not truly help, it will disturb others to no good effect. Therefore not mentioning the faults of others is the practice of bodhisattvas. ~ 17th Karmapa