-

Comment May 17, 2015

-

Hard to find a good person

Comment May 17, 2015 -

Without self interest…

Comment May 17, 2015 -

What do Koalas eat?

Comment May 17, 2015Eucalyptus leaves is the only food koalas eat. Although the leaves are poisonous to most animals, they have special bacteria that live in their stomachs to break down and digest them. Their diet includes up to one pound of leaves a day.

The koala has special teeth adapted for their eucalyptus diet. The majority of their front and back teeth act like scissors to chop the leaves into pieces suitable for digestion. Eucalyptus leaves have a fair amount of moisture hence koalas seldom drink water.

Plant specie information about eucalyptus trees indicate there are many different varieties in the wild. In fact each koala is particular about what kind they will eat. Baby koalas acquire their taste for specific varieties by adulthood. One of the main reasons koalas are endangered in some areas is the destruction of native eucalyptus forest habitats.

Eucalyptus leaves are high in fiber and low in nutrients. In addition to eating large amounts, koalas are able to survive on their diet since they have a slow metabolic system to conserve nutrients and energy. Since they have no natural predators in Australia, this adaptation is not to their disadvantage.

Koala information gathered from both wild and captive habitats suggest koalas live to be around 15 to 20 years.

Source: BearLife

-

Love on the other side

Comment May 17, 2015 -

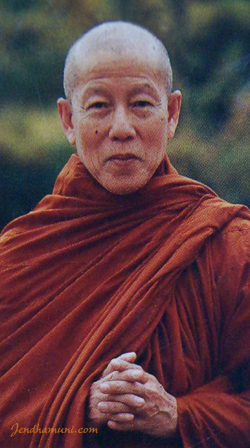

Serve others wisely

Comment May 17, 2015 -

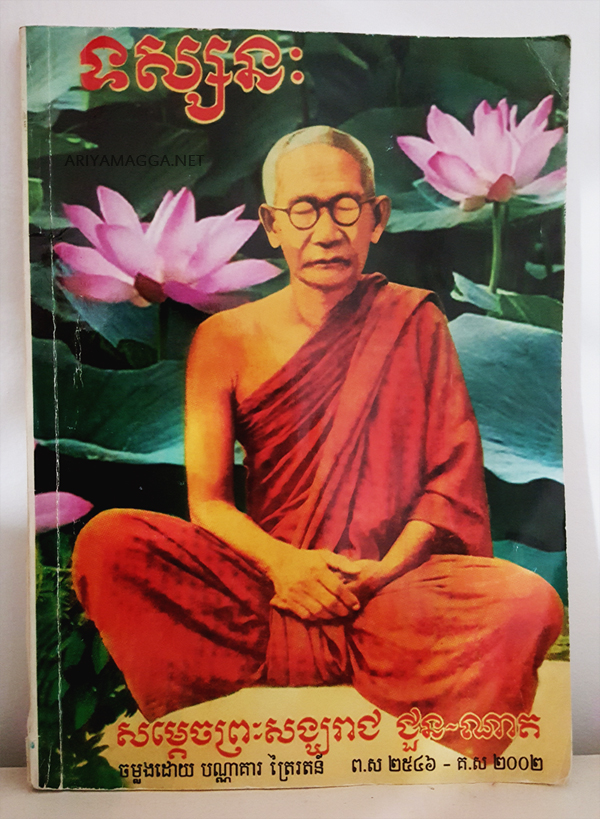

Unshakeable Peace

Comment May 17, 2015A Dhammatalk by Ajahn Chah

The whole reason for studying the Dhamma, the teachings of the Buddha, is to search for a way to transcend suffering and attain peace and happiness. Whether we study physical or mental phenomena, the mind (citta) or its psychological factors (cetasikas), it’s only when we make liberation from suffering our ultimate goal that we’re on the right path: nothing less. Suffering has a cause and conditions for its existence.

Please clearly understand that when the mind is still, it’s in its natural, normal state. As soon as the mind moves, it becomes conditioned (sankhāra). When the mind is attracted to something, it becomes conditioned. When aversion arises, it becomes conditioned. The desire to move here and there arises from conditioning. If our awareness doesn’t keep pace with these mental proliferations as they occur, the mind will chase after them and be conditioned by them. Whenever the mind moves, at that moment, it becomes a conventional reality.

So the Buddha taught us to contemplate these wavering conditions of the mind. Whenever the mind moves, it becomes unstable and impermanent (anicca), unsatisfactory (dukkha) and cannot be taken as a self (anattā). These are the three universal characteristics of all conditioned phenomena. The Buddha taught us to observe and contemplate these movements of the mind.

It’s likewise with the teaching of dependent origination (paticca-samuppāda): deluded understanding (avijjā) is the cause and condition for the arising of volitional kammic formations (sankhāra); which is the cause and condition for the arising of consciousness (viññāna); which is the cause and condition for the arising of mentality and materiality (nāma-rūpa), and so on, just as we’ve studied in the scriptures. The Buddha separated each link of the chain to make it easier to study. This is an accurate description of reality, but when this process actually occurs in real life the scholars aren’t able to keep up with what’s happening. It’s like falling from the top of a tree to come crashing down to the ground below. We have no idea how many branches we’ve passed on the way down. Similarly, when the mind is suddenly hit by a mental impression, if it delights in it, then it flies off into a good mood. It considers it good without being aware of the chain of conditions that led there. The process takes place in accordance with what is outlined in the theory, but simultaneously it goes beyond the limits of that theory.

There’s nothing that announces, ”This is delusion. These are volitional kammic formations, and that is consciousness.” The process doesn’t give the scholars a chance to read out the list as it’s happening. Although the Buddha analyzed and explained the sequence of mind moments in minute detail, to me it’s more like falling out of a tree. As we come crashing down there’s no opportunity to estimate how many feet and inches we’ve fallen. What we do know is that we’ve hit the ground with a thud and it hurts!

The mind is the same. When it falls for something, what we’re aware of is the pain. Where has all this suffering, pain, grief, and despair come from? It didn’t come from theory in a book. There isn’t anywhere where the details of our suffering are written down. Our pain won’t correspond exactly with the theory, but the two travel along the same road. So scholarship alone can’t keep pace with the reality. That’s why the Buddha taught to cultivate clear knowing for ourselves. Whatever arises, arises in this knowing. When that which knows, knows in accordance with the truth, then the mind and its psychological factors are recognized as not ours. Ultimately all these phenomena are to be discarded and thrown away as if they were rubbish. We shouldn’t cling to or give them any meaning. Continue reading

-

Ninja kitty

Comment May 16, 2015 -

Your Duties

Comment May 16, 2015 -

Little squirrel wants to be friend with kitty

Comment May 16, 2015Squirrels are familiar to almost everyone. More than 200 squirrel species live all over the world, with the notable exception of Australia. The tiniest squirrel is the aptly named African pygmy squirrel—only five inches (thirteen centimeters) long from nose to tail. Others reach sizes shocking to those who are only familiar with common tree squirrels. The Indian giant squirrel is three feet (almost a meter) long. Like other rodents, squirrels have four front teeth that never stop growing so they don’t wear down from the constant gnawing. Source: National Geographic