-

Comment June 7, 2015

-

Everyone needs a person

Comment June 7, 2015 -

The way we live our lives

Comment June 6, 2015From the Buddhist point of view—and not just Buddhist point of view—nature does not pollute itself. If it is polluted, it is because people are polluting it. Obviously, we have polluted the air and the global environment which is why we have created the problem. I feel if we human beings have done something wrong to make it so bad, it is up to human beings to correct it, since it affects all sentient beings. This is the karma of the situation from the Buddhist point of view. Whatever kind of action we take, we will have to experience a corresponding kind of result. The climate issue is a very clear case of this. We can create a very bad, negative situation for ourselves or we can create a very pleasant situation for ourselves. Whether it is the planet, society, the local environment or relationships between people – this is how actions and reactions affect each other. The phenomenon comes precisely from our incorrect way of doing things, which is to say, without considering the effect of our actions. If we want to enjoy the world around us, for our lifetime and for future generations, we must do something to improve it.

There are predictions that the outcome will be or could be like this or like that, but there is nothing definite. There is just the indication, ‘if you act like this, then it could be like that. However, if you act like this, it can be better’. If people want to change their behaviour, the world can become better. Even in very negative dark ages, there could be periods of time that are positive and good. That has been predicted. Therefore, from the Buddhist point of view, how the world becomes depends on the people living there and how they act. If human society degenerates and the world becomes worse and worse, what is happening is that peoples’ negative emotions become very raw. They act, aggressively, greedily, negatively, violently. That is how the world becomes worse. War, famine, diseases, environmental catastrophe and diminishing lifespan develop from that. If our actions or reactions improve – we cease killing, lying, deceiving, and stealing from each other – from the Buddhist point of view, both the human and ecological situation will increasingly improve. The way we live our lives and the way we react to each other affects not just human beings, but our natural environment, the world we live in.

by Ringu Tulku Rinpoche

Source: Ecological Buddhism -

For the sake of the world

Comment June 6, 2015‘Greed is also ignorance…We lose the overall view. We almost stop thinking we are part of anything at all’

There is a Sanskrit verse:

For the sake of the world you should sacrifice your country.

For the sake of the country you should sacrifice your village.

For the sake of your village you should sacrifice your family.

For the sake of your family you should sacrifice yourself.Well, it appears the opposite attitude is prevalent nowadays:

For the sake of your country you sacrifice the world.

For the sake of your village you sacrifice your country.

For the sake of your family you sacrifice your village.

For the sake of yourself you sacrifice your family.

When that kind of situation has come about, we think “If I feel it is somehow beneficial for me, or if I get more money for a certain time, I do not care if the planet is going to the dogs or not.” That is a root problem; basically it is ignorance. We think our own welfare is assured because we get money or power or whatever. Yet we live in this world and actually if the world is gone, where will we use our ‘profit’?by Ringu Tulku Rinpoche

Source: Ecological Buddhism -

“Not Sure!” – The Standard of the Noble Ones

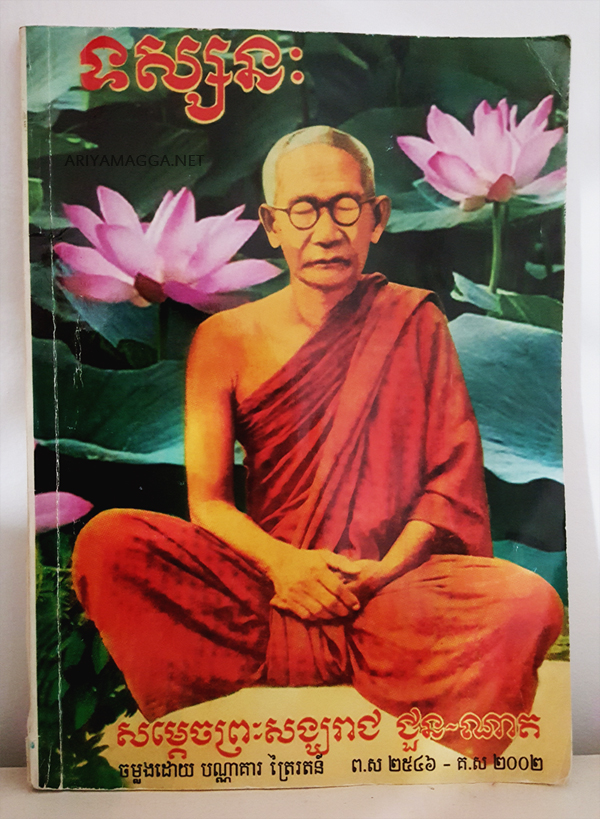

Comment June 6, 2015A Dhammatalk by Ajahn Chah

There was once a Western monk, a student of mine. Whenever he saw Thai monks and novices disrobing he would say, ”Oh, what a shame! Why do they do that? Why do so many of the Thai monks and novices disrobe?” He was shocked. He would get saddened at the disrobing of the Thai monks and novices, because he had only just come into contact with Buddhism. He was inspired, he was resolute. Going forth as a monk was the only thing to do, he thought he’d never disrobe. Whoever disrobed was a fool. He’d see the Thais taking on the robes at the beginning of the Rains Retreat as monks and novices and then disrobing at the end of it… ”Oh, how sad! I feel so sorry for those Thai monks and novices. How could they do such a thing?”

Well, as time went by some of the Western monks began to disrobe, so he came to see it as something not so important after all. At first, when he had just begun to practice, he was excited about it. He thought that it was a really important thing, to become a monk. He thought it would be easy.

When people are inspired it all seems to be so right and good. There’s nothing there to gauge their feelings by, so they go ahead and decide for themselves. But they don’t really know what practice is. Those who do know will have a thoroughly firm foundation within their hearts – but even so they don’t need to advertise it.

As for myself, when I was first ordained I didn’t actually do much practice, but I had a lot of faith. I don’t know why, maybe it was there from birth. The monks and novices who went forth together with me, come the end of the Rains, all disrobed. I thought to myself, ”Eh? What is it with these people?” However, I didn’t dare say anything to them because I wasn’t yet sure of my own feelings, I was too stirred up. But within me I felt that they were all foolish. ”It’s difficult to go forth, easy to disrobe. These guys don’t have much merit, they think that the way of the world is more useful than the way of Dhamma.” I thought like this but I didn’t say anything, I just watched my own mind.

I’d see the monks who’d gone forth with me disrobing one after the other. Sometimes they’d dress up and come back to the monastery to show off. I’d see them and think they were crazy, but they thought they looked snappy. When you disrobe you have to do this and that… I’d think to myself that that way of thinking was wrong. I wouldn’t say it, though, because I myself was still an uncertain quantity. I still wasn’t sure how long my faith would last.

When my friends had all disrobed I dropped all concern, there was nobody left to concern myself with. I picked up the pātimokkha2 and got stuck into learning that. There was nobody left to distract me and waste my time, so I put my heart into the practice. Still I didn’t say anything because I felt that to practice all one’s life, maybe seventy, eighty or even ninety years, and to keep up a persistent effort, without slackening up or losing one’s resolve, seemed like an extremely difficult thing to do.

Those who went forth would go forth, those who disrobed would disrobe. I’d just watch it all. I didn’t concern myself whether they stayed or went. I’d watch my friends leave, but the feeling I had within me was that these people didn’t see clearly. That Western monk probably thought like that. He’d see people become monks for only one Rains Retreat, and get upset.

Later on he reached a stage we call… bored; bored with the Holy Life. He let go of the practice and eventually disrobed.

”Why are you disrobing? Before, when you saw the Thai monks disrobing you’d say, ‘Oh, what a shame! How sad, how pitiful.’ Now, when you yourself want to disrobe, why don’t you feel sorry now?”

He didn’t answer. He just grinned sheepishly. Continue reading

-

The tail

Comment June 6, 2015 There is a story about a princess who had a small eye problem that she felt was really bad. Being the king’s daughter, she was rather spoiled and kept crying all the time. When the doctors wanted to apply medicine, she would invariably refuse any medical treatment and kept touching the sore spot on her eye. In this way it became worse and worse, until finally the king proclaimed a large reward for whoever could cure his daughter. After some time, a man arrived who claimed to be a famous physician, but actually was not even a doctor.

There is a story about a princess who had a small eye problem that she felt was really bad. Being the king’s daughter, she was rather spoiled and kept crying all the time. When the doctors wanted to apply medicine, she would invariably refuse any medical treatment and kept touching the sore spot on her eye. In this way it became worse and worse, until finally the king proclaimed a large reward for whoever could cure his daughter. After some time, a man arrived who claimed to be a famous physician, but actually was not even a doctor.He declared that he could definitely cure the princess and was admitted to her chamber. After he had examined her, he exclaimed, “Oh, I’m so sorry!” “What is it?” the princess inquired. The doctor said, “There is nothing much wrong with your eye, but there is something else that is really serious.” The princess was alarmed and asked, “What on earth is so serious?” He hesitated and said, “It is really bad. I shouldn’t tell you about it.” No matter how much she insisted, he refused to tell her, saying that he could not speak without the king’s permission.

When the king arrived, the doctor was still reluctant to reveal his findings. Finally the king commanded, “Tell us what is wrong. Whatever it is, you have to tell us!” At last the doctor said, “Well, the eye will get better within a few days – that is no problem. The big problem is that the princess will grow a tail, which will become at least nine fathoms long. It may start growing very soon. If she can detect the first moment it appears, I might be able to prevent it from growing.” At this news everyone was deeply concerned. And the princess, what did she do? She stayed in bed, day and night, directing all her attention to detecting when the tail might appear. Thus, after a few days, her eye got well.

This shows how we usually react. We focus on our little problem and it becomes the center around which everything else revolves. So far, we have done this repeatedly, life after life. We think, “My wishes, my interests, my likes and dislikes come first!” As long as we function on this basis, we will remain unchanged. Driven by impulses of desire and rejection, we will travel the roads of samsara without finding a way out. As long as attachment and aversion are our sources of living and drive us onward, we cannot rest.

From Daring Steps toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Buddhism, by Ringu Tulku Rinpoche

-

Turtle bites puppy’s tongue

Comment June 6, 2015Turtles have good eyesight and an excellent sense of smell. Hearing and sense of touch are both good and even the shell contains nerve endings. The shell of a turtle is made up of 60 different bones all connected together. The top domed part of a turtle’s shell is called the carapace and the bottom underlying part is called the plastron. Source: AnimalPlanet

-

Kitty loves the box

Comment June 6, 2015This box-loving aspect of a cat’s personality has long puzzled their human carers, and it’s also caught the attention of scientists. Researchers, who published their findings in Applied Animal Behaviour Science, investigated whether hiding in boxes might reduce stress for cats in animal shelters.

While most species of dog can adapt to shelter environments relatively quickly, cats often experience high levels of stress. Previous studies have shown that cats prefer areas where they have the ability to hide, but until now scientists have not studied whether so-called “hiding enrichment” might benefit a cat’s sense of well-being and specifically if providing boxes for cats to hide in might help to ease those turbulent first few weeks in a new shelter. By Steve Williams, Care2

-

To be freed from self-importance

Comment June 6, 2015 -

Value judgments

Comment June 6, 2015