-

Lamp in the darkness Comment September 24, 2015 -

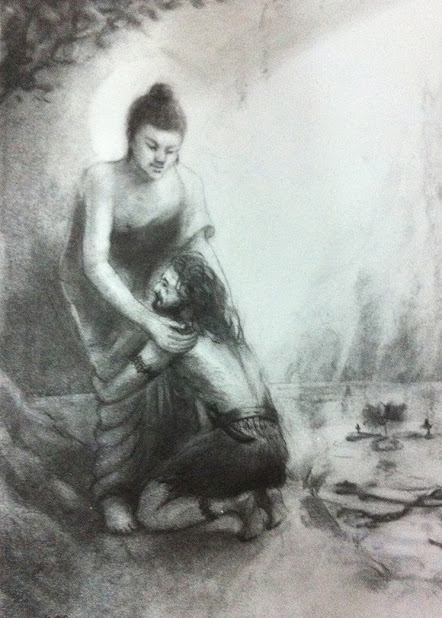

Practicing love and compassion in an impartial way Comment September 24, 2015The practices of loving kindness and compassion are incredibly relevant for everyone. Moreover, training in these qualities provides a common bridge between all different religions and areas of our world society. No matter whether we are people who teach a spiritual path or someone else, everybody can practice love and compassion, but it is important that we do so in an impartial way. ~ 17th Karmapa

-

Inner peace is the key 168 September 24, 2015 -

Puppy playing with kitty Comment September 23, 2015Female cats are typically right-pawed while male cats are typically left-pawed. A cat’s cerebral cortex (the part of the brain in charge of cognitive information processing) has 300 million neurons, compared with a dog’s 160 million. Source: Buzzfeed

-

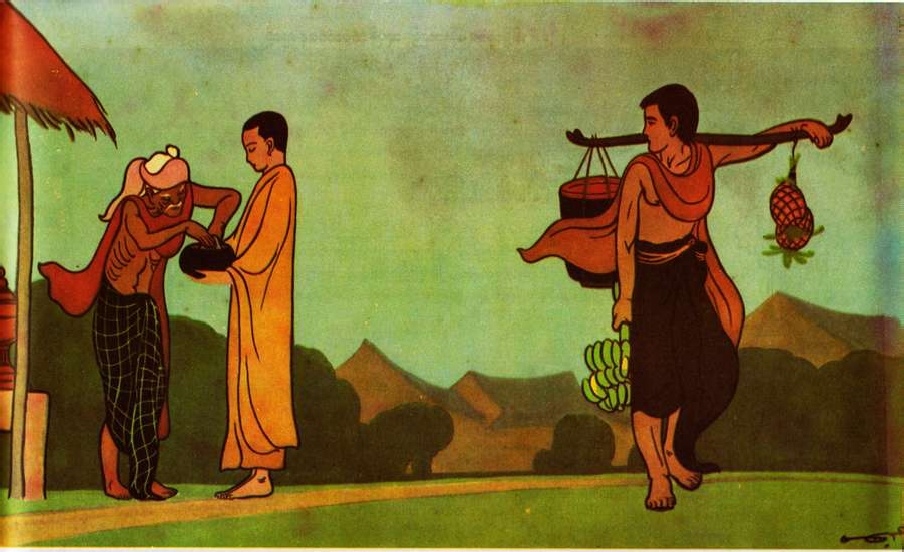

Miss no single opportunity Comment September 23, 2015Miss no single opportunity of making some small sacrifice, here by a smiling look, there by a kindly word; always doing the smallest right and doing it all for love. ~Unknown

RFA/Uon Chhin

-

What metta isn’t Comment September 22, 2015

There are many myths and misunderstandings about metta, or lovingkindness.

Simply because the word metta is not found in English — and because there isn’t an exact equivalent — it’s possible to think that the emotion itself is something strange and unusual.

It’s possible for us to confuse metta with other emotions.

It’s also possible for us to think that since metta is part of a spiritual path it must be something very exalted and distant, and not something that we’ve ever experienced.

Here are some explanations of what metta is not:

Metta isn’t the same thing as feeling good, although when we feel metta we do feel more complete, and usually feel more joyful and happy. But it’s possible to feel good and for that not to be metta. We can feel good, but be rather selfish and inconsiderate, for example. Metta has a quality of caring about others.

Metta isn’t self-sacrifice. A metta-full individual is not someone who always puts others before themselves. Metta has a quality of appreciation, and we need to learn to appreciate ourselves as well as others.

Metta isn’t something unknown. We all experience Metta. Every time you feel pleasure in seeing someone do well, or are patient with someone who’s a bit difficult, or are considerate and ask someone what they think, you’re experiencing Metta.

Metta isn’t denying your experience. To practice Metta doesn’t mean “being nice” in a false way. It means that even if you don’t like someone, you can still have their welfare at heart.

Metta isn’t all or nothing. Metta exists in degrees, and can be expressed in such simple ways as simple as politeness and courtesy.

Source: http://www.wildmind.org

-

What metta is Comment September 22, 2015

Flood in Camobdia. RFA photo

Metta is an attitude of recognizing that all sentient beings (that is, all beings that are capable of feeling), can feel good or feel bad, and that all, given the choice, will choose the former over the latter.

Metta is a recognition of the most basic solidarity that we have with others, this sharing of a common aspiration to find fulfillment and escape suffering.

Metta is empathy. It’s the willingness to see the world from another’s point of view: to walk a mile in another person’s shoes.

Metta is the desire that all sentient beings be well, or at least the ones we’re currently thinking about or in contact with. It’s wishing others well.

Metta is friendliness, consideration, kindness, generosity.

Metta is an attitude rather than just a feeling. It’s an attitude of friendliness.Metta is the basis for compassion. When our Metta meets another’s suffering, then our Metta transforms into compassion.

Metta is the basis for shared joy. When our Metta meets with another’s happiness or good fortune, then it transmutes into an empathetic joyfulness.Metta is boundless. We can feel Metta for any sentient being, regardless of gender, race, or nationality.

Metta is the most fulfilling emotional state that we can know. It’s the fulfillment of the emotional development of every being.

It’s our inherent potential. To wish another well is to wish that they be in a state of experiencing Metta.Metta is the answer to almost every problem the world faces today. Money won’t do it. Technology won’t do it. Metta will.

Source: http://www.wildmind.org

-

Human nature being what it is Comment September 22, 2015

RFA photo/Sireymuny

By Ven. Dr K. Sri Dhammananda Nayaka Maha Thera

Human nature being what it is, all of us are inclined to put the blame on others for our own shortcomings or misfortunes. Do you ever give a thought for a moment that you yourself can be responsible for your own problems? Your sorrows and miseries are not caused by a family curse that is handed down from one generation to the next. Nor are they caused by the original sin of some ancestor who has returned from beyond the grave to haunt you. Nor are your sorrow and miseries created by a god or by a devil. Your sorrow is caused by yourself. Your sorrow is your own making. You are your own liberator.

You must learn to shoulder the responsibilities of your life and to admit your own weakness without blaming or disturbing others. Remember the old saying :

“The uncultured man always blames others; the semi cultured man blames himself and the fully-cultured man blames neither.”

As a cultured being, you must learn to solve your own problems without blaming others. If each person would try to correct himself, there would not be any trouble in this world. But many people do not make any effort to realize that they themselves are responsible for many misfortunes that befall them. They prefer to find scapegoats.They look outside themselves for the source of their troubles because they are reluctant to admit their own weaknesses.

Man’s mind is given to so much self-deceit that he does not want to admit his own weakness. He will try to find some excuse to justify his action and to create an illusion that he is blameless. If a man really wants to be free, he must have the courage to admit his own weakness.

The Buddha says: “Easily seen are others’ faults; hard indeed it is to see one’s own fault.”

You must develop the courage to admit when you have fallen victim to your weakness. You must admit when you are in the wrong. Do not follow the uncultured who always blames others. Do not use other people as your scapegoat – this is most despicable. Remember that you may fool some of the people some of the time, but not all the people all of the time.

The Buddha says: “The fool who does not admit he is a fool, is a real fool. And the fool who admits he is a fool is wise to that extent.”

Admit your own weakness. Do not blame others. You must realize that you are responsible for the miseries and the difficulties that come to you. You must understand that your way of thinking also creates the conditions that give rise to your difficulties. You must appreciate that at all times, you are responsible for whatever comes to you.

“It is not that something is wrong with the world, but something is wrong with us.”

You Are responsible For Your Relationship With Others

Remember that whatever happens to you cannot feel hurt if you know how to keep a balanced mind. You are hurt only by the mental attitude that you adopt towards yourself and towards others. If you show a loving attitude towards others, you will receive a loving attitude in return. If you show hatred, you will undoubtedly never receive love in return. An angry man breathes out poison and he hurts himself more than others. Anyone who is wise not to be angered by anger will not be hurt. Remember that no one can hurt you unless you allow others to hurt you. Of another person blames or scolds you, but you follow the Dhamma (truth), then that Dhamma will protect you from unjust attacks.

The Buddha says: “Whoever harms a harmless person, one pure and guiltless, upon that very fool the evil recoils like fine dust thrown against the wind.”

If you allow others to fulfill their wishes in hurting you, you are responsible.

Blame Not Others – Accept Responsible

Source: buddhistbugs.blogspot.com

-

Right Speech Comment September 22, 2015By Thanissaro Bhikkhu

For many of us, right speech is the most difficult of the precepts to honor. Yet practicing right speech is fundamental both to helping us become trustworthy individuals and to helping us gain mastery over the mind. So choose your words – and your motives for speaking – with care. An essay by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

Right speech, explained in negative terms, means avoiding four types of harmful speech: lies (words spoken with the intent of misrepresenting the truth); divisive speech (spoken with the intent of creating rifts between people); harsh speech (spoken with the intent of hurting another person’s feelings); and idle chatter (spoken with no purposeful intent at all).

Notice the focus on intent: this is where the practice of right speech intersects with the training of the mind. Before you speak, you focus on why you want to speak. This helps get you in touch with all the machinations taking place in the committee of voices running your mind. If you see any unskillful motives lurking behind the committee’s decisions, you veto them. As a result, you become more aware of yourself, more honest with yourself, more firm with yourself. You also save yourself from saying things that you’ll later regret. In this way you strengthen qualities of mind that will be helpful in meditation, at the same time avoiding any potentially painful memories that would get in the way of being attentive to the present moment when the time comes to meditate.

In positive terms, right speech means speaking in ways that are trustworthy, harmonious, comforting, and worth taking to heart. When you make a practice of these positive forms of right speech, your words become a gift to others. In response, other people will start listening more to what you say, and will be more likely to respond in kind. This gives you a sense of the power of your actions: the way you act in the present moment does shape the world of your experience. You don’t need to be a victim of past events.

For many of us, the most difficult part of practicing right speech lies in how we express our sense of humor. Especially here in America, we’re used to getting laughs with exaggeration, sarcasm, group stereotypes, and pure silliness — all classic examples of wrong speech. If people get used to these sorts of careless humor, they stop listening carefully to what we say. In this way, we cheapen our own discourse. Actually, there’s enough irony in the state of the world that we don’t need to exaggerate or be sarcastic. The greatest humorists are the ones who simply make us look directly at the way things are.

Expressing our humor in ways that are truthful, useful, and wise may require thought and effort, but when we master this sort of wit we find that the effort is well spent. We’ve sharpened our own minds and have improved our verbal environment. In this way, even our jokes become part of our practice: an opportunity to develop positive qualities of mind and to offer something of intelligent value to the people around us.

So pay close attention to what you say — and to why you say it. When you do, you’ll discover that an open mouth doesn’t have to be a mistake.

Source: http://www.esolibris.com

-

Smile — the key that fits the lock of everybody’s heart Comment September 22, 2015

S_̅_̅_̅̅()

S_̅_̅_̅̅()