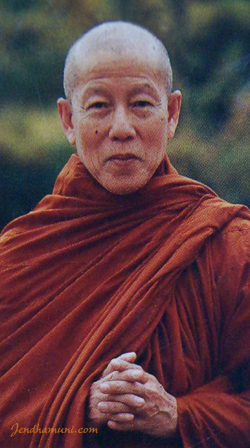

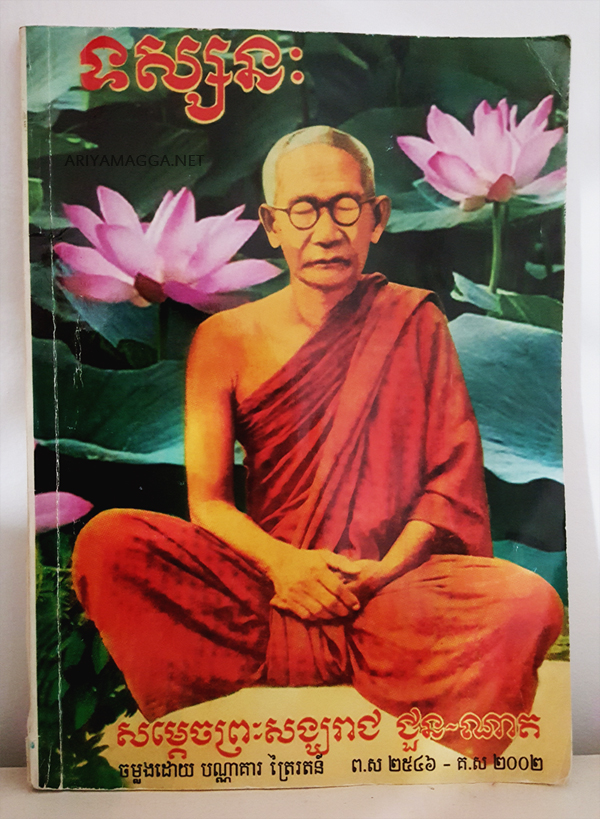

A Dhamma talk by Ajahn Chah

To calm the mind means to find the right balance. If you try to force your mind too much it goes too far; if you don’t try enough it doesn’t get there, it misses the point of balance.

Normally the mind isn’t still, it’s moving all the time. We must strengthen the mind. Making the mind strong and making the body strong are not the same. To make the body strong we have to exercise it, to push it, in order to make it strong, but to make the mind strong means to make it peaceful, not to go thinking of this and that. For most of us the mind has never been peaceful, it has never had the energy of samādhi2, so we must establish it within a boundary. We sit in meditation, staying with the ‘one who knows’.

If we force our breath to be too long or too short, we’re not balanced, the mind won’t become peaceful. It’s like when we first start to use a pedal sewing machine. At first we just practise pedalling the machine to get our coordination right, before we actually sew anything. Following the breath is similar. We don’t get concerned over how long or short, weak or strong it is, we just note it. We simply let it be, following the natural breathing.

When it’s balanced, we take the breathing as our meditation object. When we breathe in, the beginning of the breath is at the nose-tip, the middle of the breath at the chest and the end of the breath at the abdomen. This is the path of the breath. When we breathe out, the beginning of the breath is at the abdomen, the middle at the chest and the end at the nose-tip. Simply take note of this path of the breath at the nosetip, the chest and the abdomen, then at the abdomen, the chest and the tip of the nose. We take note of these three points in order to make the mind firm, to limit mental activity so that mindfulness and self-awareness can easily arise.

When our attention settles on these three points, we can let them go and note the in and out breathing, concentrating solely at the nose-tip or the upper lip, where the air passes on its in and out passage. We don’t have to follow the breath, just to establish mindfulness in front of us at the nose-tip, and note the breath at this one point – entering, leaving, entering, leaving. Continue reading →