Through meditation

As gold purified in a furnace loses its impurities and achieves its own true nature, the mind gets rid of the impurities of the attributes of delusion, attachment and purity through meditation and attains Reality. ~Adi Shankara

As gold purified in a furnace loses its impurities and achieves its own true nature, the mind gets rid of the impurities of the attributes of delusion, attachment and purity through meditation and attains Reality. ~Adi Shankara

RFA/Chin Chetha

Verse 19: Though he recites much the Sacred Texts (Tipitaka), but is negligent and does not practise according to the Dhamma, like a cowherd who counts the cattle of others, he has no share in the benefits of the life of a bhikkhu (i.e., Magga-phala).

Verse 20: Though he recites only a little of the Sacred Texts (Tipitaka), but practises according to the Dhamma, eradicating passion, ill will and ignorance, clearly comprehending the Dhamma, with his mind freed from moral defilements and no longer clinging to this world or to the next, he shares the benefits of the life of a bhikkhu (i.e., Magga-phala).

1. suvimuttacitto: Mind freed from moral defilements; this has been achieved through perfect practice and clear comprehension of the Dhamma.

2. sa bhagava samannassa hoti: lit., shares the benefits of the life of a samana (a bhikkhu). According to the Commentary, in this context, it means, “Shares the benefits of Magga-phala.”

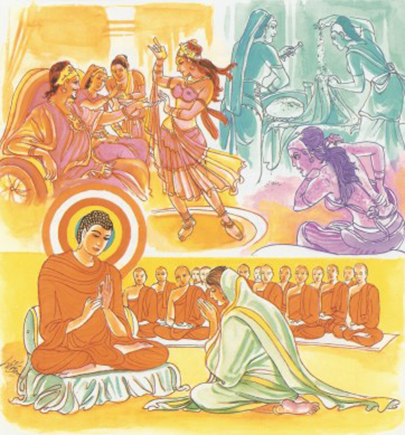

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verses (19) and (20) of this book, with reference to two bhikkhus who were friends.

Once there were two friends of noble family, two bhikkhus from Savatthi. One of them learned the Tipitaka and was very proficient in reciting and preaching the sacred texts. He taught five hundred bhikkhus and became the instructor of eighteen groups of bhikkhus. The other bhikkhu striving diligently and ardently in the course of Insight Meditation attained arahatship together with Analytical Insight.

On one occasion, when the second bhikkhu came to pay homage to the Buddha, at the Jetavana monastery, the two bhikkhus met. The master of the Tipitaka did not realize that the other had already become an arahat. He looked down on the other, thinking that this old bhikkhu knew very little of the sacred texts, not even one out of the five Nikayas or one out of the three Pitakas. So he thought of putting questions to the other, and thus embarass him. The Buddha knew about his unkind intention and he also knew that as a result of giving trouble to such a noble disciple of his, the learned bhikkhu would be reborn in a lower world.

So, out of compassion, the Buddha visited the two bhikkhus to prevent the scholar from questioning the other bhikkhu. The Buddha himself did the questioning. He put questions on jhanas and maggas to the master of the Tipitaka; but he could not answer them because he had not practised what he had taught. The other bhikkhu, having practised the Dhamma and having attained arahatship, could answer all the questions. The Buddha praised the one who practised the Dhamma (i.e., a vipassaka), but not a single word of praise was spoken for the learned scholar (i.e., a ganthika).

The resident disciples could not understand why the Buddha had words of praise for the old bhikkhu and not for their learned teacher. So, the Buddha explained the matter to them. The scholar who knows a great deal but does not practise in accordance with the Dhamma is like a cowherd, who looks after the cows for wages, while the one who practises in accordance with the Dhamrna is like the owner who enjoys the five kinds of produce of the cows*. Thus, the scholar enjoys only the services rendered to him by his pupils but not the benefits of Magga-phala. The other bhikkhu, though he knows little and recites only a little of the sacred texts, having clearly comprehended the essence of the Dhamma and having practised diligently and strenuously, is an ‘anudhammacari’**, who has eradicated passion, ill will and ignorance. His mind being totally freed from moral delilements and from all attachments to this world as well as to the next, he truly shares the benefits of Magga-phala.

Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 19: Though he recites much the Sacred Texts (Tipitaka), but is negligent and does not practise according to the Dhamma, like a cowherd who counts the cattle of others, he has no share in the benefits of the life of a bhikkhu (i.e., Magga-phala).

Verse 20: Though he recites only a little of the Sacred Texts (Tipitaka), but practises according to the Dhamma, eradicating passion, ill will and ignorance, clearly comprehending the Dhamma, with his mind freed from moral defilements and no longer clinging to this world or to the next, he shares the benefits of the life of a bhikkhu (i.e., Magga-phala). Continue reading

If you want to conquer the anxiety of life, live in the moment, live in the breath. ~Amit Ray

Don’t fill your time with worry – fix what you can and let the rest take care of itself.

~Unknown

What Buddhism Teaches About Anger

By Barbara O’Brien, About.com Guide

Anger. Rage. Fury. Wrath. Whatever you call it, it happens to all of us, including Buddhists. However much we value loving kindness, we Buddhists are still human beings, and sometimes we get angry. What does Buddhism teach about anger?

Anger is one of the three poisons – the other two are greed and ignorance – that are the primary causes of the cycle of samsara and rebirth. Purifying ourselves of anger is essential to Buddhist practice. Further, in Buddhism there is no such thing as “righteous” or “justifiable” anger. All anger is a fetter to realization.

Yet even highly realized masters admit they sometimes get angry. This means that for most of us, not getting angry is not a realistic option. We will get angry. What then do we do with our anger?

First, Admit You Are Angry

This may sound silly, but how many times have you met someone who clearly was angry, but who insisted he was not? For some reason, some people resist admitting to themselves that they are angry. This is not skillful. You can’t very well deal with something that you won’t admit is there.

Buddhism teaches mindfulness. Being mindful of ourselves is part of that. When an unpleasant emotion or thought arises, do not suppress it, run away from it, or deny it. Instead, observe it and fully acknowledge it. Being deeply honest with yourself about yourself is essential to Buddhism.

What Makes You Angry?

It’s important to understand that anger is something created by yourself. It didn’t come swooping out of the ether to infect you. We tend to think that anger is caused by something outside ourselves, such as other people or frustrating events. But my first Zen teacher used to say, “No one makes you angry. You make yourself angry.”

Buddhism teaches us that anger is created by mind. However, when you are dealing with your own anger, you should be more specific. Anger challenges us to look deeply into ourselves. Most of the time, anger is self-defensive. It arises from unresolved fears or when our ego-buttons are pushed.

As Buddhists we recognize that ego, fear and anger are insubstantial and ephemeral, not “real.” They’re ghosts, in a sense. Allowing anger to control our actions amounts to being bossed around by ghosts.

Anger Is Self-Indulgent

Anger is unpleasant but seductive. In this interview with Bill Moyer, Pema Chodron says that anger has a hook. “There’s something delicious about finding fault with something,” she said. Especially when our egos are involved (which is nearly always the case), we may protect our anger. We justify it and even feed it.

Buddhism teaches that anger is never justified, however. Our practice is to cultivate metta, a loving kindness toward all beings that is free of selfish attachment. “All beings” includes the guy who just cut you off at the exit ramp, the co-worker who takes credit for your ideas, and even someone close and trusted who betrays you. Continue reading

(One who has done good deeds rejoices here and rejoices afterwards too; he rejoices in both places. Thinking “I have done good deeds” he rejoices, he rejoices all the more having gone to a happy existence.)

The Master while residing at Jetavana delivered this religious discourse beginning with “Here (in this world) one who has done good deeds rejoices” in connection with Sumanadet Savatthi, two thousand monks used to take their meals daily in the house of Anathapindika and a similar number in the house of the eminent female-devotee Visakha. Whosoever wished to give alms in Savatthi, they used to do so after getting permission of these two. What was the reason for this? Even though a sum of a hundred thousand was spent in charity, the monks used to ask:

“Has Anathapindika or Visakha come to our alms-hall?” If told, “They have not”, they used to express words of disapproval saying “What sort of a charity is this?” The fact was that both of them (Anathapindika and Visakha) knew exceedingly well what the congregation of monks liked, as also what ought to be done befitting the occasion. When they supervised, the monks could take food according to their liking, and so all those who wished to give alms used to take those two with them. As a result, they (Anathapindika and Visakha) could not get the opportunity to serve the monks in their own homes.

Thereupon, pondering as to who could take her place and entertain the congregation of monks with food, and finding her son’s daughter, Visakha made her take the place. She started serving food to the congregation of monks in Visakha’s house. Anathapindika too made his eldest daughter, Mahasubhadda by name, officiate in his stead. While attending to the monks, she used to listen to the Dhamma. She became a Sotapanna and went to the house of her husband. Then he (Anathapindika) put Cullasubhadda in her place. She too acting likewise became a Sotapanna and went to her husband’s house. Then his youngest daughter Sumanadevi was assigned the place. She, however, attained the fruition of sakadagami. Though she was only a young maiden, she became afflicted with so severe a disease that she stopped taking her food and wishing to see her father sent for him.

Anathapindika received the message while in an almshouse. At once he returned and asked her what the matter was. She said to him, ‘Brother, what is it?’ He said ‘Dear, are you talking in delirium?’ Replied she, ‘Brother, I am not delirious.’ He asked, ‘Dear, are you in fear?’ and she replied, ‘No, I am not, brother.’ Saying only these words she passed away. Though a Sotapanna, the banker was unable to bear the grief that arose in him for his daughter and after having had the funeral rites of his daughter performed, approached the Master weeping. Being asked: Householder, what makes you come sad and depressed, weeping with a tearful face?’, he replied ‘Lord, my daughter Sumanadevi has passed away.’ ‘But, why do you lament? Isn’t death common to all beings?’ ‘Lord, this I am aware of, but the fact that my daughter, who was so conscious of a sense of shame and fear of evil, was not able to maintain her self-possession at the time of her death and passed away talking in delirium, has made me very depressed.’ ‘But, noble banker, what was it that she said?’

‘When I addressed her as “Dear Sumana”, she said “What is it, dear brother? “*

‘Then when I asked her “Dear, are you talking in delirium ?”, she replied “I am not talking in delirium, brother”.

‘When I asked her “Are you in fear, dear?”, she replied “Brother, I am not”. Saying this much she passed away.’

Thereupon the Master told him, Noble banker, your daughter was not talking in delirium.’ When asked why she spoke like that, the Master replied, ‘It is because of your lower spiritual position; indeed your daughter held a higher position than you did in the attainment of the path (magga) and fruition (phala); you are only a Sotapanna but your daughter was a sakadagami, it was because of her higher position in the attainment of path and fruition that she spoke to you in that way’. The banker asked, ‘Is that so Lord ?’, and the Master affirmed saying ‘It is so’. When asked ‘Where is she reborn at present?’ the Master said, ‘In the Tusita heaven, O householder’. Then the banker made this remark, ‘Lord, having rejoiced here in this world in the midst of kinsmen, now again, after passing away, my daughter has been reborn in a place of joy.’ Thereupon the Master told him, ‘Yes banker, the diligent, whether they are householders or samanas, surely rejoice in this world as well as in the next’, and uttered this stanza.

Idha nandati, pecca nandati,

katapunno ubhayattha nandati.

“punnam me katan” ti nandati

bhiyyo nandatisuggatim gato. Continue reading

True love never dies…

My little sister Alanthara passed a way unexpectedly two years ago, today — November 3rd, 2013. My wonderful father joined her 13 months later. They both were buried next to each other. ~Jendhamuni

My little sister Alanthara and my dad.

Some people think that it’s holding on that makes one strong; sometimes it’s letting go. A break up is like a broken mirror. It is better to leave it broken than hurt yourself trying to fix it. ~Unknown

At the Parlee Farms.

Love is a shelter in a raging storm. Love is peace in the middle of a war, and if we try to leave, may God send angels to lock the doors. No, love is not a fight, but it’s something worth fighting for. ~Warren Barfield

While we try to teach our children all about life,

Our children teach us what life is all about.

~Angela Schwindt

RFA/Men Sothyr