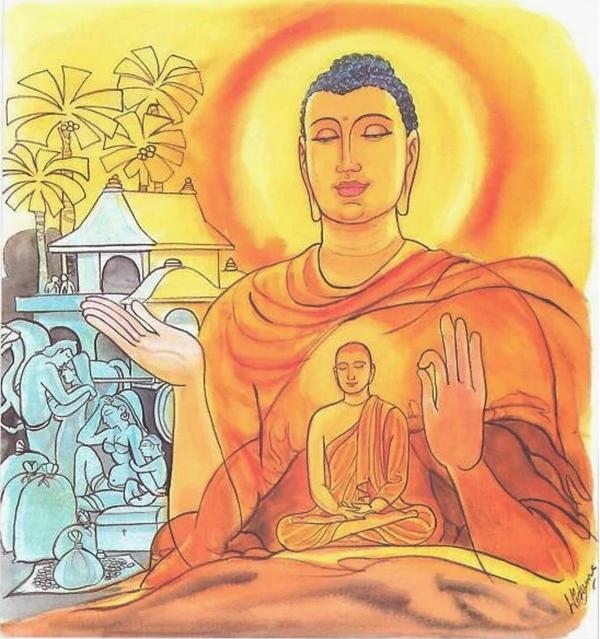

Visakha Puja: Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and passing into Nibbana

Celebrating the birth, enlightenment and parinibbana of the Lord Buddha at Wat Kiryvongsa Bopharam, Peace Meditation Center on May 4, 2023.

Celebrating the birth, enlightenment and parinibbana of the Lord Buddha at Wat Kiryvongsa Bopharam, Peace Meditation Center on May 4, 2023.

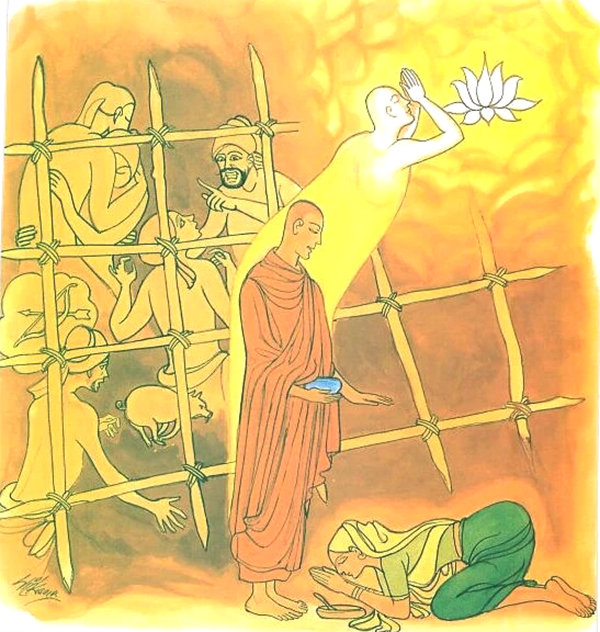

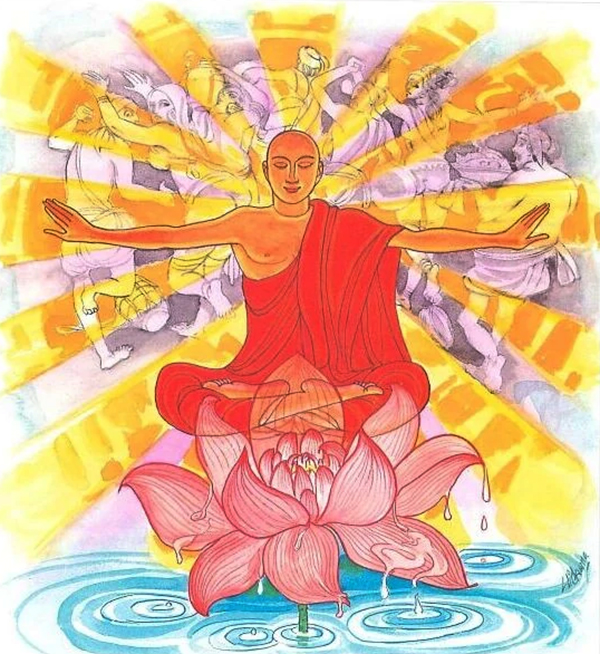

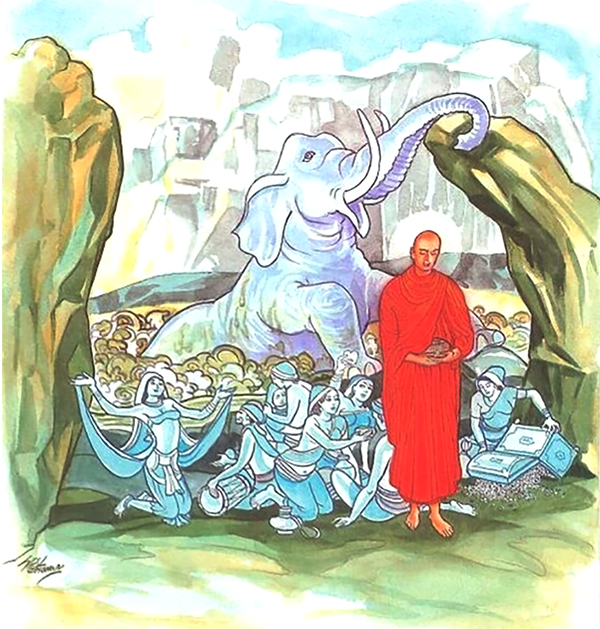

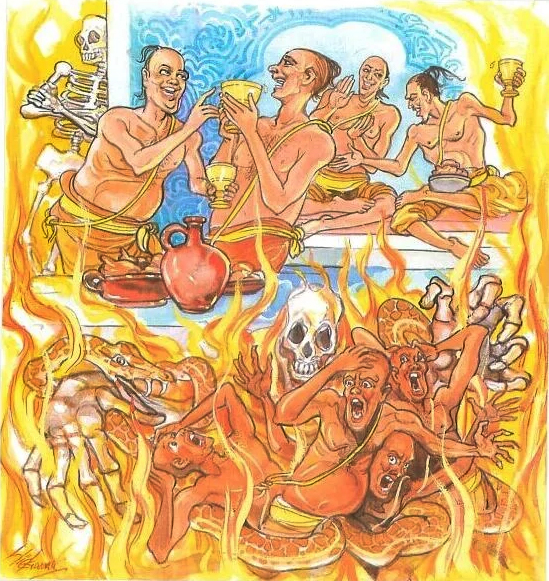

Visakha Puja Day (Vesak) is one of the most important days in Buddhism and for Buddhists. It is the day Buddhists assemble to commemorate the life of the Buddha, and to give reverence to His purity, profound wisdom and immense compassion for all humankind and living beings by reflecting and using His teachings as guidelines for their lives. Visakha Puja Day also marks the anniversary of three significant events in the life of the Buddha – His Birth, Enlightenment, and Attainment of Complete Nibbana – that occurred on the 15th day of the 6th waxing moon. — Dhammakaya